59220 I am Uluru – CVR

I AM ULURU: A FAMILY’S STORY

It is customary in many indigenous communities, and in Anangu culture, that the names of the deceased not be mentioned and their images not be reproduced until such time as the family deems it appropriate.

Anangu, and all people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island descent, are advised that this publication contains the names and images of some people who have died.

I am Uluru: A Family’s Story

By Jen Cowley – with the Uluru family

“I am Uluru: A Family’s Story” gives a glimpse into the hitherto untold story of the family entrusted as traditional owners and custodians of arguably Australia’s most iconic landmark – Uluru (formerly known as Ayers Rock) and that country, which has been home to the Anangu (people of the Central Desert) for tens of thousands of years.

The story begins at the relatively recent point in history known as “first contact” and follows the highs and lows of the family’s (and all Anangu’s) struggle to adapt to the increasingly whitefella world while still holding on to deeply traditional faith and way of life.

Told with an intoxicating mix of personal recollection – in their own words – and well-researched and sensitively crafted creative and contextual narrative, the book takes the reader on a journey of discovery and enlightenment but makes neither judgement nor conclusion – the reader is left to digest the knowledge and reach their own understanding.

This book is not an exercise in finger pointing – it is simply one unique family’s contribution to the cultural landscape that has for too long been misunderstood, misrepresented and marginalised through a lack of understanding. The book aims to open up as much of a traditional world as possible so that others might come to a place of greater understanding about the value of maintaining that sacred culture.

Crafted over the course of three years of intensive contact on country with the elders of the Uluru family, the book has been described as “an important work”, “a great read”, “beautifully written”, “an emotional roller coaster” and “something all Australians should read”.

First-person accounts from Uluru family members across three generations are stitched together with carefully researched contextual narrative and sensitively crafted creative storytelling to form a unique and well-rounded overview of a remarkable family’s history.

“I am Uluru” is not only a thought-provoking and page-turning read, it is a document of national cultural significance and a tool of genuine reconciliation.

ISBN: 9780648412007

Copyright: 2018 © The Uluru Family

Published: October 2018

Launch: Uluru NT in December 2018 with the Uluru family.

Funded by: Commonwealth Department of Communities and The Arts

Printed by: The OMNE Group – 0417 685 997 – info@omne.com.au

Available from: The author – PREFERRED – (through the email below)

Or through Amazon – https://www.amazon.com.au/I-am-Uluru-Jen-Cowley/dp/0648412008

Or through Booktopia – https://www.booktopia.com.au/i-am-uluru-jen-cowley/book/9780648412007.html

Jen Cowley (Author) – jencowley@live.com

Media Enquiries: Jen Cowley (Author) – 0439 022 133 – jencowley@live.com

Jen Cowley acts in a voluntary capacity as conduit for the Uluru family – proceeds returned to community for the preservation and maintenance of culture and language.

****

Foreword

Ulurulanguru Alice Springs-lakutu ankula kulilkatiningina book pala palunya. nyangatja tjinguru tjukurpa pulka mulapa. Anangu tjuta kulira nintiringkuntjaku. Anangu maru tjuta kulintjaku Anangu tjutaku Tjukurpa kulintjaku. Ara irititja tjuta kulintjaku. , paper palatja tjukurpa wiru, read-amilara kulini, tjinguru kulilku. nyaa kulini tjituru-tjituru ngnpa yaaltji yaaltji mala ngaraku? Mutitjululanguru ankula kulira kulira kulilkatiningi, munta tjituru-tjituru. Ngarakatinguna ilany pakara. palula tjituru-tjituru ngarangi panya, milanypa pakanyangka. Uti nkarangku kulintjaku. Walka tjunkuntjaku ngaranyi. Tjungungku nyinara palyantjaku. nyaa purunypa wangkanyi ka wall ngaranyi ngururpa. Ngapartji ngapartji nyuntu nganananya putu kulini nganana ngapartji putu kulini.

I was driving from Uluru to Alice Springs and I was thinking about this book. I was thinking, “This is a big book.” It is important for people to understand; to understand Anangu, to understand Tjukurpa. To understand history. This book will be history. If it’s read, maybe people will understand. I got sad while I was thinking. I was driving from Mutitjulu and I was thinking all the way and I got sad. What does the future hold? I had to pull over because it made me cry, you know? I had tears coming out. It’s important for people to understand.We need to write it all down. We can work together. Otherwise there’s a big wall in between us – I can’t come across and you can’t come across.

Sammy Wilson (Tjama Uluru) 2018

Preface

There’s a certain colour that’s unique to the red centre of Australia; a particular shade of purplish pink that paints the landscape for just a few tantalising minutes as the sun sets over the central desert. It’s a blush that comes in those few precious seconds after the day’s grand finale – a blazing, fiery sunset that makes Uluru look like a chunk of heaven that’s fallen from the sun itself.

You can’t see this astonishing veil of colour by looking directly at it. It disappears under direct gaze. You have to look to the side, avert your eyes, use your peripheral vision, to see it properly. Those lucky enough to be able to glimpse it will witness for those few minutes the true essence, the heart, of the red centre’s palette.

So it is with Tjukurpa – the ancient Anangu faith – and the same is true of the Uluru family’s story. Look directly at it and you won’t see its majesty.

Not until you squint the eye of your consciousness can you take in the entire view and see it not as a seemingly disjointed collection of tales and thoughts and experiences and recollections, but as a whole beautiful picture. The Uluru family story is like a hand-made quilt with the individual pieces all a different shade, a different texture, a different size. Not until it is stitched together does its collective beauty and meaning become clear. And this is just a small part of a much larger quilt.

When I was invited by members of the Uluru family to help tell their story, I was still far from the point of comprehending the necessity of using peripheral vision to take in the entire view. They knew this. I didn’t. But they also knew that, with their guidance, I would come to understand the nuances and intricacies of the Anangu way and the retelling of the story would be richer for that learning. It is only with hindsight that I can fully appreciate the enormity of both their trust and the privilege afforded by that initial invitation.

The Uluru family’s motivation for undertaking to tell their story is twofold. With the passage of time and the subsequently inevitable erosion of traditional ways, the recording of stories and recollections is a race against the generational clock. The family’s elders fear the loss of their knowledge and history, and their fervent wish is to preserve – in the modern way of the written word – as much as they can before it is forever lost to coming generations.

But the family also acknowledges a well-intentioned thirst for understanding from the wider, non-Anangu world. The Anangu way is to share and the Uluru family accepts that inviting visitors into their world is also a way to help preserve their precious culture and knowledge, just as they have accepted the need to embrace the contemporary world in which they now live.

Their hope is that through fostering a greater understanding of their culture, others will help with its preservation and so the Uluru family has chosen, for the first time in a forum such as this, to open up as much of their traditional world as is possible so that others might come to understand why certain elements of Anangu culture must remain secret and sacred if they are to remain safe.

Inherent in this cultural landscape are challenges that make the conventional account of a family’s story an impossibility.

It is important, if the family’s aim of nurturing a deeper understanding of their story is to be achieved, that some of these challenges be explained ahead of a dive into its pages. While the contextual narrative that underscores the retelling of the stories will help, there are some things the reader will need to know about the parts to fully appreciate the whole.

The recollections and information on which this story is based came largely from elders for whom English is often a third, fourth or even fifth tongue, so while the translations were as accurate as possible there are certain nuances of language that have required some tweaking. Like most indigenous Australian languages, the Anangu word was not written until only very recent times. Many Anangu are able to listen to and understand English far more clearly than they are able to speak it.

For a story such as this, the eliciting of feelings and emotions are integral, however it is difficult to accurately or appropriately translate the word “feeling”. There is a word, “kulini”, that encompasses a number of perspectives – it means to listen, hear, think about/consider, decide, know about, understand, remember, have a premonition from a sensation in the body, and yes, to feel. Ask directly “How did you feel?” and Anangu will wonder which of these perspectives to draw on. Thanks to the close proximity to which Anangu live in community, they are so finely tuned to the feelings of others they rarely need to ask the question. Some imagination and gentle creativity have therefore been necessary to fill in those emotional gaps.

Hindsight is also not part of the Anangu way, so asking for reflections is difficult, as is eliciting recollections of what Uluru family members were thinking at a particular time. Westerners tend to analyse everything; culturally we are looking for the “whys” and looking for answers. Anangu preoccupations are different. They live in the present.

With this in mind, it is ineffective to approach a project such as this using a conventional chronological framework. Dates, times and deadlines have little relevance for Anangu. For instance, there is no direct translation in their languages for the word “day” – the best we could approximate was “sun’s up” – so piecing together a family timeline has been tricky, as has the unique and complex Anangu system of kinship and family. This may at times make the story seem disjointed to those who are used to conventional historical accounts, but dates and times are not the essence of this story.

It is similarly not the Anangu culture to learn by asking questions, nor to teach by responding to direct questions. The elders set the pace of learning and in doing so, teach the fundamental art of listening. Our conditioning makes questioning a widely accepted process but for Anangu, it can be experienced as mildly offensive in the sense that it can feel like a challenge to their way of teaching and to their knowledge itself. Prolonged and repeated questioning, therefore, becomes something of a visceral invasion. It’s about respecting boundaries and it was important throughout this process to allow the Uluru family tell their stories in their way.

The passing on of knowledge comes not chronologically but at a time and a pace the elders believe is appropriate.

While this was initially frustrating for a journalist (particularly of the female variety) whose default setting is to fire direct questions based on the “who, what, when, where, why” approach, the beauty and effectiveness of their way soon became clear. They knew far better than I what I needed to know, but more importantly, when I needed and was ready to know it. They taught me when I was ready to learn and as a result the knowledge and stories gathered have far deeper meaning. I was then able to stitch together what had for so long felt like a mish-mash of disjointed patchwork pieces.

I am neither anthropologist nor sociologist, linguist nor demographer. Neither am I a conventional historian.

I am a storyteller for the Uluru family.

And this is their story.

Jen Cowley, October 2018

Copies of I am Uluru: A family’s story, are available through Woodslane Distributors (02) 8445 2300 and Amazon Australia – search “I am Uluru”.

You can also message me, Jen Cowley, through the contact details listed on this website – email jencowley@live.com

Palya.

******

Grandpa’s Hat cover image – original illustration by Mark Horton

Grandpa’s Hat

Grandpa’s Hat – written by Jen Cowley and illustrated by Mark Horton – is the story of Jennywren and all her favourite animals, who help her discover that although her Grandpa is gone, he doesn’t have to be forgotten.

Grandpa’s Hat is now in it’s third print run, having first been developed in 2015 with the support of the combined Rotary Clubs of Dubbo and Coonabarabran as a resource for the National Association of Loss and Grief NSW Inc. (NALAG) to help parents and carers guide children through the difficult time of loss and grief.

Proceeds from the sale of the book go to help NALAG (National Association for Loss and Grief) – a not-for-profit, volunteer-supported organisation – to continue the work it does in supporting people who are grieving.

https://www.nalag.org.au/product-page/grandpashat

(Pictured with Trudy Hanson, Former CEO of NALAG (National Association for Loss and Grief))

Copies of Grandpa’s Hat – which includes a gentle guide for parents and carers – are available from the NALAG Centre for Loss and Grief – http://www.nalag.org, or by messaging Jen through the Grandpa’s Hat Facebook site – http://www.facebook.com/pg/Grandpas-Hat.

*************

That’s the “official” blurb, but the story behind Grandpa’s Hat is very personal – the following article might help to explain:

Tjintu Tjatu Kaltukatjarala (Days in Docker River)

A book of photographs and stories reflecting life in remote Northern Territory Aboriginal community Kaltukatjara (Docker River) – produced and published in 2016 with the input and consultation of the community (Kungka Kutjara Aboriginal Corporation) as a community development project in support of the people of Kaltukatjara, with all proceeds from the sale of the book being reinvested in the community. The book is presented in both English, and Pitjantjatjara language (with translations by Rameth Thomas).

Launched: Apr 16, 2016

Available through Wintjiri Gallery at Yulara (Ayers Rock Resort), Northern Territory or by contacting the author through this site.

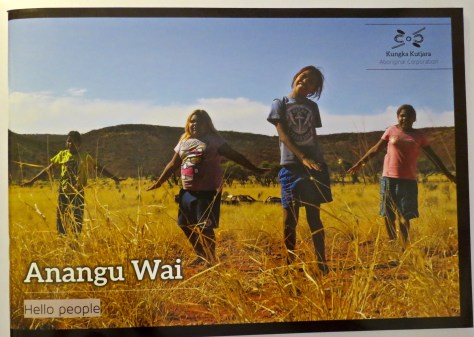

Anangu Wai (Hello, People)

A book of photographs and stories reflecting life in remote Northern Territory Aboriginal communities of Mutitjulu and Imanpa Kaltukatjara – produced and published in consultation and with the input of the Anangu and the communities (through Kungka Kutjara Aboriginal Corporation in conjunction with Anangu Jobs) as a community development project in support of the people of Imanpa, Mutitjulu and Kaltukatjara with all proceeds from the sale of the book being reinvested in the communities. The book is presented in both English, and Pitjantjatjara language (with translations by Rameth Thomas and Harry Wilson).

Kungka Kutjara Aboriginal Corporation

Launched: September 29, 2016

Available through Wintjiri Gallery at Yulara (Ayers Rock Resort), Northern Territory or by contacting the author through this site.

I was lucky enough to work with my husband, Steve (an accomplished photographer) on this project, and to have been able to include some of his shots in the book.

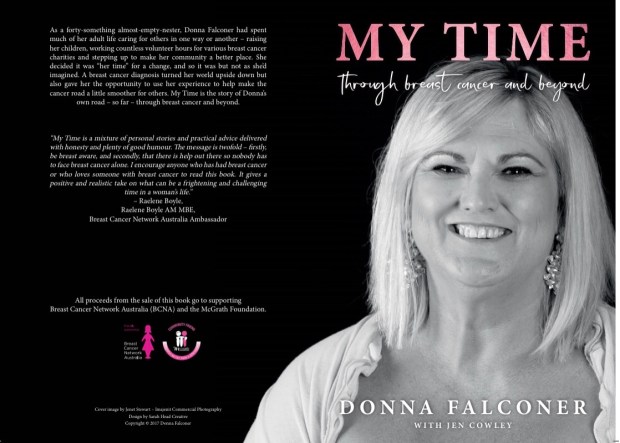

My Time: Through Breast Cancer and Beyond

“My Time is a mixture of personal stories and practical advice delivered with honesty and plenty of good humour. The message is twofold – firstly, be breast aware, and secondly, that there is help out there so nobody has to face breast cancer alone. I encourage anyone who has had breast cancer or who loves someone with breast cancer to read this book. It gives a positive and realistic take on what can be a frightening and challenging time in a woman’s life.” – from the foreword by Raelene Boyle AM MBE, Breast Cancer Network Australia Ambassador

I was thrilled and honoured to be asked by my old friend and well known regional breast cancer awareness campaigner Donna Falconer to help write her “memoir” documenting her experience (“journey” if you’d like, although that’s a seriously over-used buzz word these days) so far with battling and surviving breast cancer, and with establishing a successful charity (Pink Angels) to help raise awareness of the need for early detection of breast cancer and provide practical support to those diagnosed.

I thought I knew Donna Falconer. We’ve been friends for more than twenty years. Then she asked me to help her find the words to tell her story.

Throughout this extraordinarily personal process, I’ve come to know this equally extraordinary woman as never before.

As a professional exercise, putting oneself into the mind of another to explore and enunciate their thoughts is a unique experience. I’ve been blessed over the years to be given the opportunity to help many people share their stories but this project quickly morphed from assignment to deeply personal investment.

The trust Donna has shown me is humbling. Opening up her personal and professional life was one thing. To throw open the door to her emotional cupboard was a great leap of faith and I feel deeply privileged to have been invited into that space. I hope I’ve done her, and her remarkable story, justice.

I’m grateful not only to Donna, but to the many people who have made this memoir possible through support both financial and emotional, and through offering their own contributions.

Mostly I’m grateful that Donna not only survived her bout with breast cancer, but that she had the vision and courage to use such a deeply personal experience to help smooth some of the bumps in the cancer road for others to walk.

Launched in December 2017, the book has been described as “the gift that keeps giving” – it’s not just a great read (although I’m biased!), there’s the added (and very generous on Donna’s part) bonus that ALL proceeds directed in equal part to The McGrath Foundation and Breast Cancer Network Australia.

Here’s the blurb:

Writing projectsAs a forty-something almost-empty-nester, Donna Falconer had spent much of her adult life caring for others in one way or another – raising her children, working countless volunteer hours for various breast cancer charities and stepping up to make her community a better place. She decided it was “her time” for a change, and so it was but not as she’d imagined. A breast cancer diagnosis turned her world upside down but also gave her the opportunity to use her experience to help make the cancer road a little smoother for others.

My Time, which Donna describes as “a true team effort”, was published thanks to community support, including from the combined Rotary Clubs of Dubbo and the Dubbo RSL, gives a humorous but sensitive and insightful glimpse into the breast cancer experience and has been described by readers as “a bloody good read” and “a must for anyone whether you’ve had breast cancer or not”.

Praise for My Time:

“A good read with humour and sadness.” “Couldn’t put it down.” “Loved this book. You are an inspiration.” “It was great. Didn’t want it to end.”

If you’d like a copy of the book, contact me or go to the Groovy Booby Bus Facebook page.